Written by Kenny Mack

Picture by Maria Oswalt

“Restorative justice is a process to involve, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense to collectively identify and address harms, needs and obligations in order to heal and put things as right as possible.”––Howard Zehr

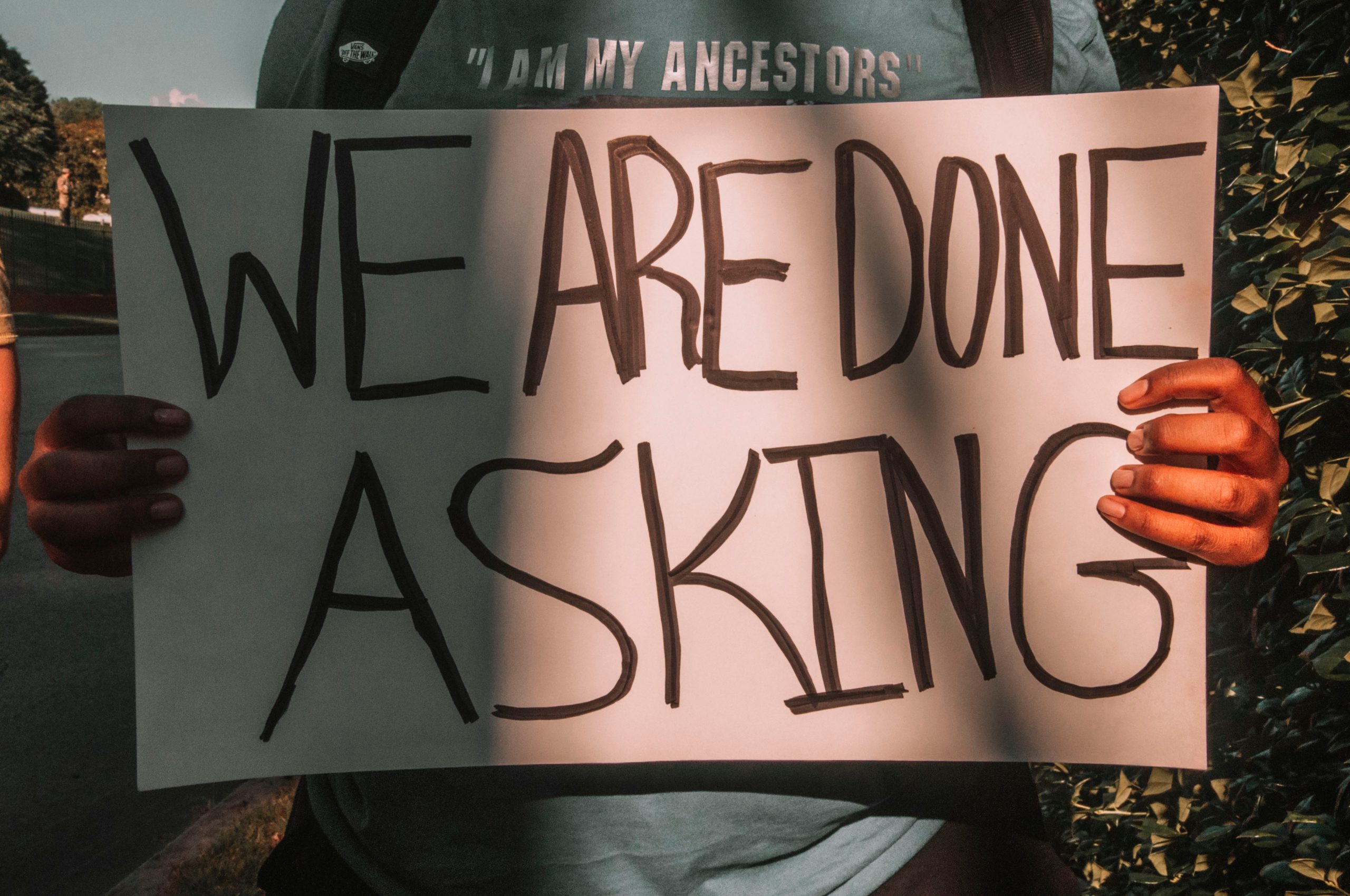

THIS IS AMERICA

Despite the fact that cannabis is legal in some form in 35 states and the District of Columbia, harms are being done all over our country as poor communities of color are still being fatally over-policed because of the “War on Drugs.” From 19-year-old Ramarley Graham in the Bronx, to 21-year-old Trevon Cole in Las Vegas, to 43-year-old Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, encounters with police over low-level cannabis offenses continue to cost the next generation of Black and Brown men their lives.

We’ve all seen stories of officers like Jeronimo Yanez, who claimed the smell of cannabis made him fear for his life when he killed Philando Castile in front of his girlfriend and her (now-traumatized) daughter by stating, “I thought if he [Castile] has the guts and the audacity to smoke marijuana in front of the five-year-old girl…then what care does he give about me?” We’ve all heard about officers like Darren Wilson, who wasn’t indicted for killing 18-year-old Michael Brown after a grand jury heard the teenager’s cannabis use might have caused aggressive behavior. And we all know police are much more likely to target and arrest people living in poor communities of color for selling, possessing, and using the same drugs that people in other communities are selling, possessing, and using.

What we don’t often get is historical perspective to provide context for the criminalization of Black and Brown life – or the uneven and unequal enforcement of cannabis prohibition we’re experiencing today.

For example, it’s impossible to discount the impact that the practice of redlining has had on residential and commercial real estate markets in poor communities of color. Keeping property values artificially low provides a disincentive for investment, reduces economic activity in those neighborhoods, and negatively impacts the potential for creating generational wealth. With the budget framework for most cities and towns using real estate tax revenue to fund public services, that left infrastructure in decay, garbage un-collected, and turned large sections of the urban landscape into unhealthy, blighted food deserts with polluted air, dirty water, and a diminished quality of life.

These harms were compounded as the 50-year-long War on Drugs predictably resulted in the mass-removal of working-age men from communities of color. Taken in combination with relentlessly negative portrayals in movies, TV, news, and advertising, this made Black and Brown men all-but-invisible in American life while being hunted by police in their own neighborhoods. It also left the next generation of Black and Brown kids with a striking absence of male role models in mass-media, or in their day-to-day lives.

THIS IS RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

In the context of crime and punishment, restorative justice is all about needs and roles. Among its fundamental concepts is to view a crime as a violation of people and interpersonal relationships. It requires identifying stakeholders who were victimized by the crime, then centering the process around meeting their needs. This obligates the person in the offender role to be held accountable, to gain a complete understanding of the consequences of their violation, and to do as much as possible to make things right. Crucially, it also requires the offender to take responsibility for restoring whatever harm was done to the victims.

When it comes to five decades of systemic devaluation of real property, systemic disregard for residents and business owners, systemic extraction of manpower, and systemic dehumanization of millions of people in poor communities of color, doing restorative justice is more of a challenge. After all, if the “crime” is federal policy, and the offender is the Government of the United States of America, then there really can’t be any “punishment.” Guided by the principles of restorative justice, the next Congress and the Biden/Harris administration owes these communities answers to the following questions:

Who has been harmed by cannabis prohibition?

What was the nature and duration of that harm?

Who benefited from the harm?

What actions need to be taken to restore the harm done?

The required taking of responsibility would necessarily be symbolic; with Congress and the President making some kind of statement about the consequences of prohibition by acknowledging that it has been enforced unequally, accepting that different community members have been impacted in different ways, and committing to action that meets the needs of stakeholder victims.

Accountability would mean acknowledging past harms, encouraging empathy and personal responsibility, and creating accessible systems of engagement with community members. This obligation would necessarily have to be met through federal cannabis policy that improves on the shortcomings in existing state laws, and creates an equitable interstate cannabis marketplace designed around the needs of stakeholder victims in communities most impacted by prohibition. Primarily, the needs of the people whose knowledge and expertise built, maintains, and controls a domestic job-creation juggernaut that will soon be bigger than the NFL.

Leadership must come from the federal government because the sad, immoral fact is that the economic and regulatory playing field in states where cannabis has been legalized is almost hopelessly tilted in favor of wealthy and well-connected operators. Given its support in Congress and the White House, the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act (MORE) can serve as a starting point for developing federal policy that ensures an equitable marketplace and adequate restoration of over-policed communities.

THIS IS THE TIME

Surely, a federal government which can address historic wrongs through anti-discrimination, fair housing, and affirmative action laws can do the same with regard to cannabis prohibition and its impact on people living in poor communities of color. To truly atone for a half-century of institutionalized racism and structural inequality, these neighborhoods can’t just be repaired, they must be restored. The creation of an equitable interstate cannabis marketplace would be a very big step in the right direction, but it won’t be easy.

The type of person who has worked their way into a career as a legislator or regulator usually doesn’t have a frame of reference to help guide their thinking on this issue. Most often, the view from the state capital or City Hall is through a prohibitionist lens which sees cannabis as the demon weed in a dangerous business run by violent Black and Brown criminals – and has no problem adding barriers to entry and costs of compliance that are so high as to make the industry inaccessible to anyone who isn’t wealthy or well-connected.

The reality is that most providers in the legacy cannabis market are not violent criminals. They’re more like a couple we all know, and who we’ll call Malik and Jalisa. These two are in a committed long-term relationship, they’re raising a family together, and they’re running their own small business (sourcing product, maintaining quality control, managing supply chain disruption, satisfying customers, and balancing the books) in a way that isn’t technically legal.

In state after state, people are coming out to support ballot measures forcing Governors and legislatures to change the law and legalize Malik and Jalisa’s business. The will of the voters is clear: Create a marketplace in which legacy providers can become respectable capitalists. But once lawmakers have been lobbied by law enforcement groups and big business, the inevitable (and undemocratic) result is a marketplace in which respectable capitalists can replace legacy providers.

This repeated state-level failure to see the voters’ will be done is a big part of the reason why federal cannabis policy must be rooted in restorative justice while being centered around the needs of people like Malik and Jalisa, their families, and the neighborhoods where they live. As victims of over-policing, these stakeholder groups deserve the chance to build (or re-build) community by caring for their neighbors in need without involving the heavy hand of law enforcement. They should also be able to rest assured that an even harsher and more unforgiving version of prohibition isn’t coming for them in the future.

How To Advocate For Cannabis Safety Without Harming The Movement

Leave a Reply