The electoral college has come under fire since the 2000 U.S. presidential election. The system in place since this country was founded has been branded as unfair, disproportionate, and even racist, reports The Atlantic. Now, a new compact may hasten the electoral college’s possible demise.

As with many current political issues, the decision to leave the electoral college in place or dismantle it has fierce defenders and opponents. With mixed reactions over what to do, will a replacement for the electoral college come into effect sooner than we think?

What is the Electoral College and NPVIC?

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) was devised by several former electors and college professors who opposed the electoral college.

Opposition to the electoral college gained traction after the 2000 election in which President George W. Bush defeated Vice President Al Gore despite losing the popular vote.

States who join the compact bind their electoral votes to the winner of the nation-wide popular vote as opposed to the winner of each individual state.

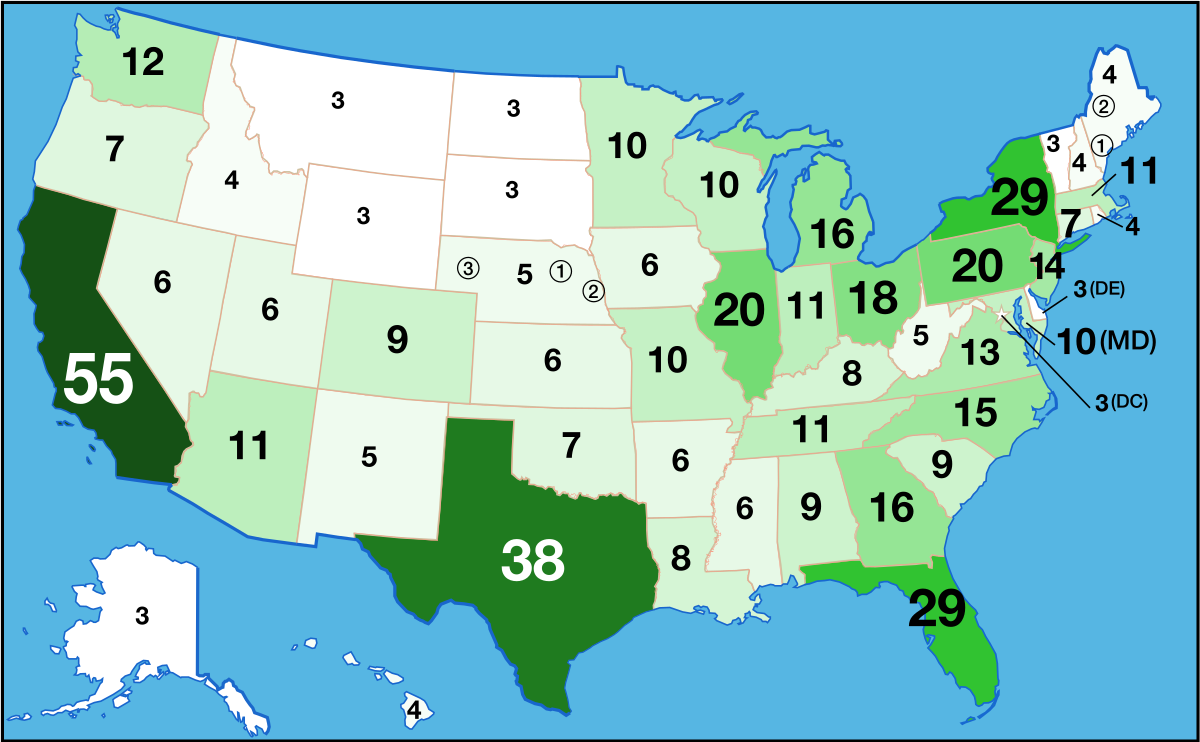

According to NBC News, the compact was first adopted by Maryland in 2007. Since then, a total of 15 states and the District of Columbia have joined the compact, totalling 196 electoral votes.

After the compact reaches 270 electoral votes, it will achieve legal force. Once the total hits 270, the majority of electoral votes would be won based on the popular vote. At this point, it becomes impossible to win the electoral college without the popular vote.

States Joining the Compact

The states that have passed the compact are reliably blue states. However, the compact is currently pending approval in Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL).

If passed in all those states, the compact would have support of a combined 304 electoral votes from 21 states and D.C. This would give the compact sufficient legal force.

The future seems optimistic as just last year Colorado, Delaware, New Mexico, and Oregon all joined the compact, reports The Oregonian.

With redistricting from the 2020 Census due to take place soon, the number of delegates supporting the compact may be altered, according to NYmag.

The Electoral College Isn’t Dead

Despite the fact that more states have joined the compact, many states have also killed such bills.

The measure has failed in 18 states, according to the NCSL. These states include powerful swing states like Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. In addition, several liberal-leaning states have voted against the compact like Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and New Hampshire.

Of course, lawmakers can always re-introduce bills that support the compact. However, some states have continued to veto the bill in one legislative house after reintroduction.

For clarification, a bill becomes a law after it passes in both state houses and the state’s governor approves and signs it.

The only state to pass the compact in both houses and still not join is Nevada. According to the Nevada State Legislature, the bill was shot down after Nevada Democratic Gov. Steve Sisolak vetoed it.

But, some states joined the compact even after their governor vetoed it.

In Hawaii, for instance, Republican Gov. Linda Lingle vetoed the compact three times before the legislature overrode it. The National Popular Vote Compact site states the legislature’s override of the governor’s veto finally allowed Hawaii to join the compact.

Currently, some Republican controlled chambers have passed the compact. However, no Republican governor has signed the compact into law.

Is the NPVIC Constitutional?

The constitutionality of the NPVIC has come into question as well.

For example, the Compact Clause of the constitution prohibits any states from joining into compacts with other states.

However, reports from the Congressional Research Service found that recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings have permitted agreements between states. Citing these rulings, it is very likely that a compact would need congressional approval to achieve legal force. This is because the constitution expressly prohibits the word “compact,” necessitating congressional approval despite Supreme Court rulings on “agreements.”

The Compact Clause is the central issue concerning the compact’s legality. Opponents of the measure cite the Compact Clause to ensure state governments aren’t trumping the power of the federal government. This is essentially why the electoral college works the way it does.

To comprise the U.S. Senate, each state is equally apportioned one hundred electors, and 435 are apportioned based on each state’s population. These two factions make up the electoral college (plus three votes from D.C.) and the bicameral houses of Congress.

Ironically, this exact constitutional issue is also one of the factors that has led to the creation of the compact.

Does the Compact Favor Certain States?

Slate reports that there are essentially two arguments that explain why the electoral college is structured unfairly.

Some believe the electoral college unfairly favors small states. This belief stems from the fact that smaller states have greater representation per delegate than larger states. The mandatory apportionment of two senators to each state is the cause of this.

Others, however, believe the electoral college unfairly favors large states. Essentially, because large states comprise most of the 270 votes needed to win the presidency, some argue large swing states — Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania — are the only states subject to heavy campaigning. Usually, only five or six states decide an election as most other states are either firmly blue or red.

What’s Next?

Based on a recent uptick in support for the compact and uproar over the electoral college, it seems likely the compact will achieve the necessary 270 electoral votes.

FiveThirtyEight reports that Colorado’s entrance into the compact establishes that purple states are willing to join. Thus, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia’s pending committee hearings on joining the compact may not be as swiftly decided as in the past. Virginia, a state that tends to vote democratically in presidential elections, has advanced the measure to the state’s upper house.

Unlike the path to the presidency, however, the road to 270 may have a few obstacles past the finish line.

Congressional Research Service notes that it is possible the election process can only be altered by a constitutional amendment.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court or Congress will likely bring the NPVIC into legal force, regardless of whether the necessary number of states approve it.

By Thomas O’Connor

New Hampshire Legislature Overrode Governor’s Veto of Medical Marijuana Bill

Leave a Reply